HERCULES IN CELTIC COIN ART – MIS-INTERPRETATION OR RE-INTERPRETATION

The figure of Hercules/ Herakles is a common motif in Classical art. It features on many Greek and Roman coins and makes its way into Eastern Celtic coins too. It is quite easy to see the Celtic images simply as copies of varying skill. But on closer examination, it can be seen that, in fact, there is a divergence of not just style, but also imagery.

Firstly, however, it is important to remember that the figure of Herakles has a very long presence around the whole of the Mediterranean. The visual prototype of semi-divine hero who fights animals and monsters is perhaps earliest to emerge in the art of Mesopotamia, but it is likely to have a much older pedigree. It is one of the main templates for cultural- hero- protector- progenitor. It is related, to, but not identical with, the warrior-king archetype. That warrior-king type is clearly related to Sovereignty and the Right to Rule. It has to do with structure and order of society, supported by the warrior elite and priestly classes. Although Herakles is king of various territories throughout his life, his main exploits are those of a lone, outsider, wandering hero. The fact that he is half- god, half-human sets him aside as a liminal misfit. In fact, most of his tribulations arise from the antagonism between human and divine realms. Some Classical texts maintained that Herakles was already known to the Western Celts before contact with Greek or Roman cultures, and that he was considered a ‘First Ancestor’ figure. His adoption into Coin art is therefore wholly legitimate, even though a Classical representation tends to dominate. The loner-wild man- hero- protector is a figure that pervades myth and folklore. He tends to be immensely strong, cunning, but not the most intellectual of beings. He is fecund, violent, but a protector of family. He appears as Thor and The Dagda, where both these IE mythic types wield simple weapons, are of giant size, battle monsters and accrue a popular, likeable, bawdy nature. They are related to all sky/thunder/storm/fertility templates. Some believe that Vajrapani, the Tibetan protector yidam derives from a Herakles type, and that this also evolves into the fierce protector gods of the gateways of Chinese and Japanese Buddhist temples. They can be found in the sky-castle dwelling giants that later, more knightly heroes attempt to eradicate on their quests, ( a clear usurpation of the roles of earlier cultures by newer cultural sensibilities). The wild man tamed, or the wild man running wild, seem to be the issues being explored. Herakles himself is a complex, flawed figure, both protector/ progenitor and also destroyer. He is a summation of the difficulties of humans in wielding innate power. An ideal First Ancestor, in many respects.

It is surprising that Hercules/Herakles is not used more often at the moment as an example of fluid gender models. Depicted as the alpha male, all bulging testosterone and the like, Herakles took both male and female lovers and also spent time in a cross-dressing, gender swapping relationship.

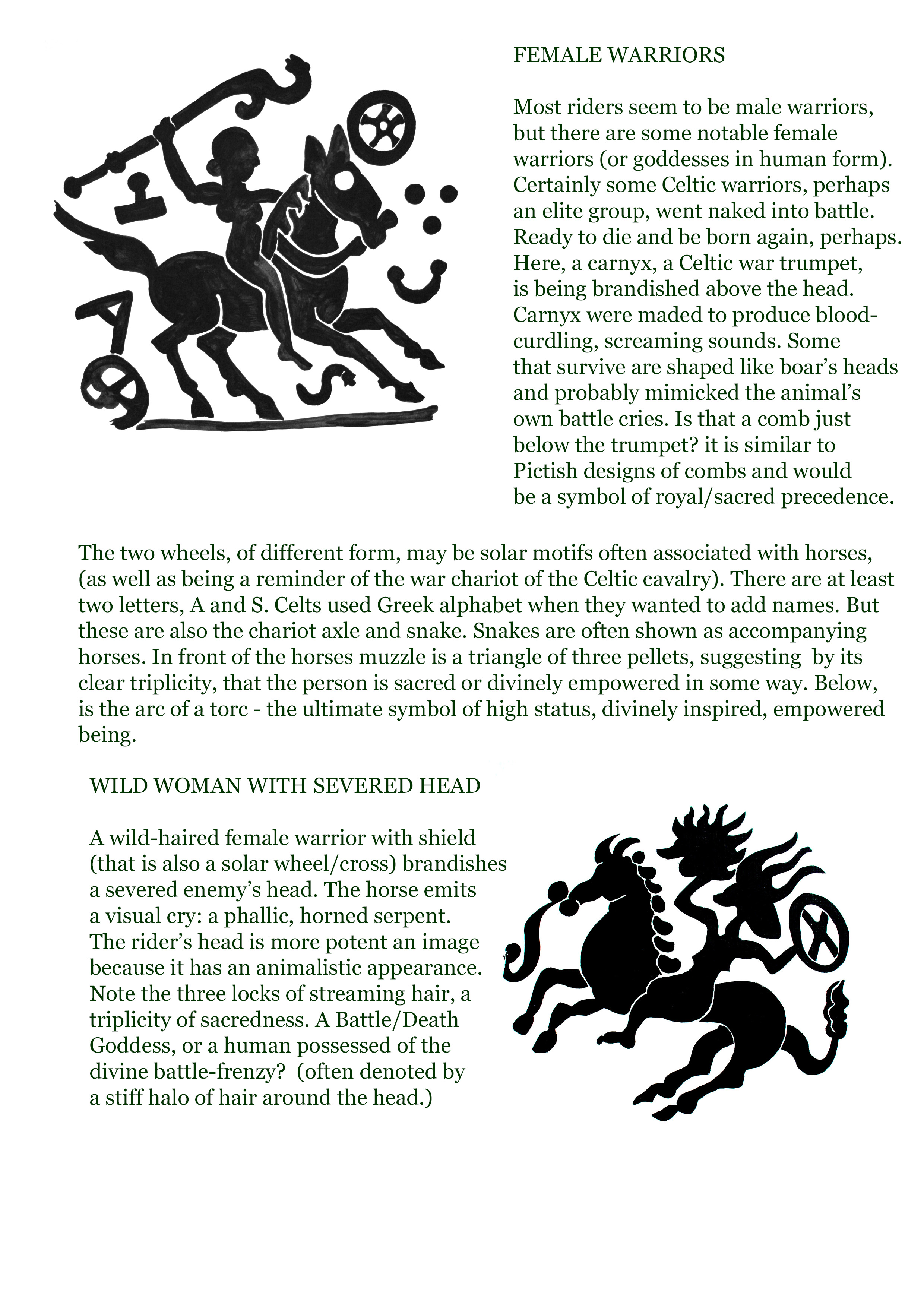

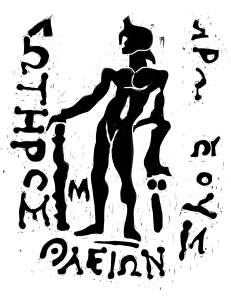

1. I have put these images in a stylistic order, starting with those that follow Classical prototypes quite closely, then moving on to those that diverge towards more clearly Celtic forms. This in no way represents the actual chronology of the coins: Classical types were probably used for a variety of reasons, such as the availability of die cutters with Classical training, political or aspirational links to a Classical culture, and so on. This image shows a well-modelled relief figure, standing contraposto, right hand resting on a large wooden club, left arm bent at the elbow holding a lion skin. The Greek text of Classical coins is more or less precise. The only move towards Celtic abstraction here is the rather, (no doubt intentional), phallic head of the lion-skin

2. Another close copy of a Classical,original. The figure has less modelling and less definition, though the contraposto with hand on hip is still clear. The Greek lettering is still important, though some of the forms are showing more interest in pattern-making.

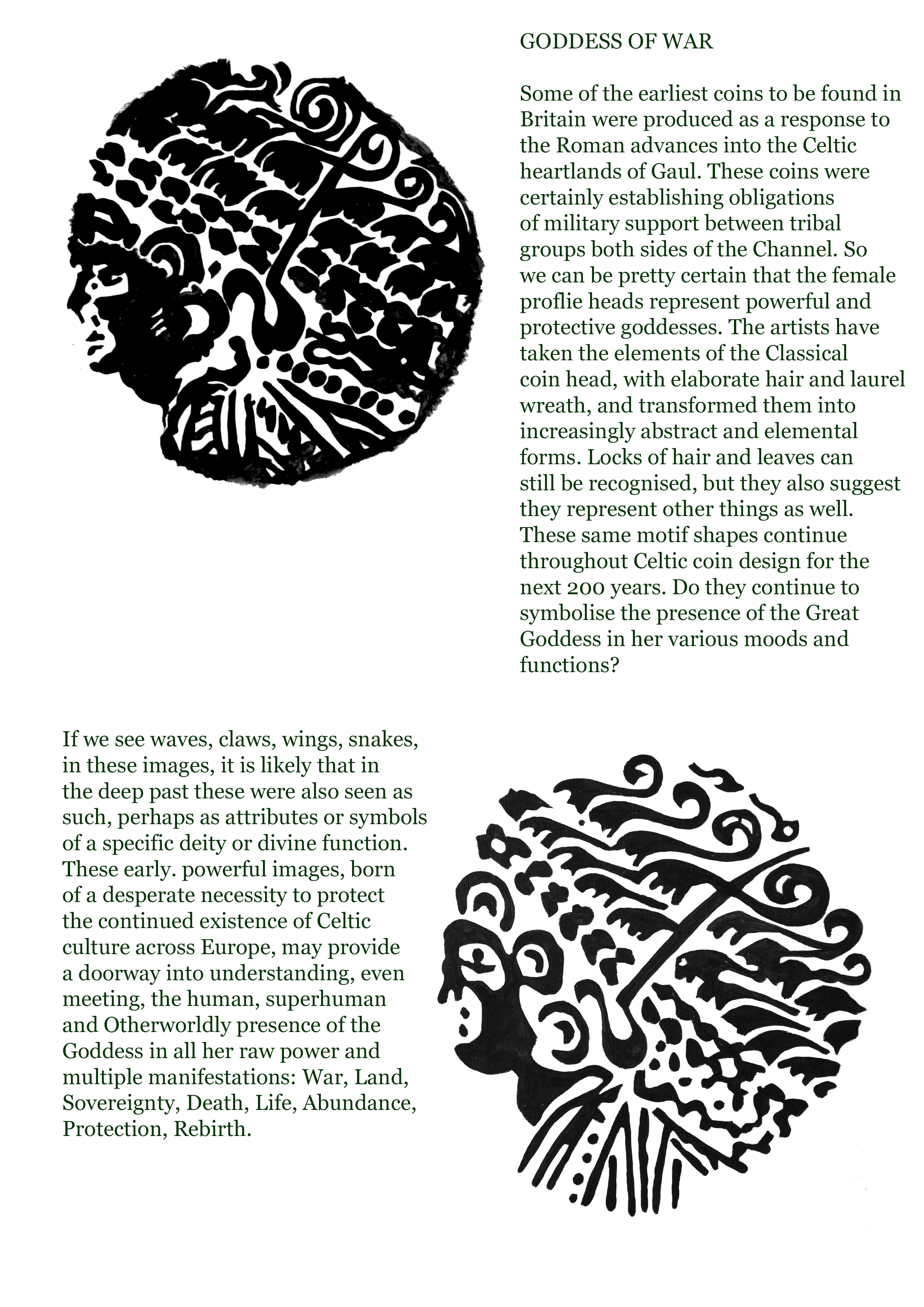

3. The Classical elements are still present here, but the artist is more interested in the curve of lines and an abstraction of forms. Much greater attention is given to the details of the club and the lion-skin. The letters become more integrated with the design, rather than simply giving a square frame to the figure. The club seems to be transforming into a fruiting branch, or a very knobbly club. The lion-skin is rendered as a three sets of pellets. Note also that there is much emphasis placed on the muscles of the upper torso and shoulders, whilst the legs are less important. The profile head is also moving away from a Classical profile, towards a more Celtic ‘staring eye’ type.

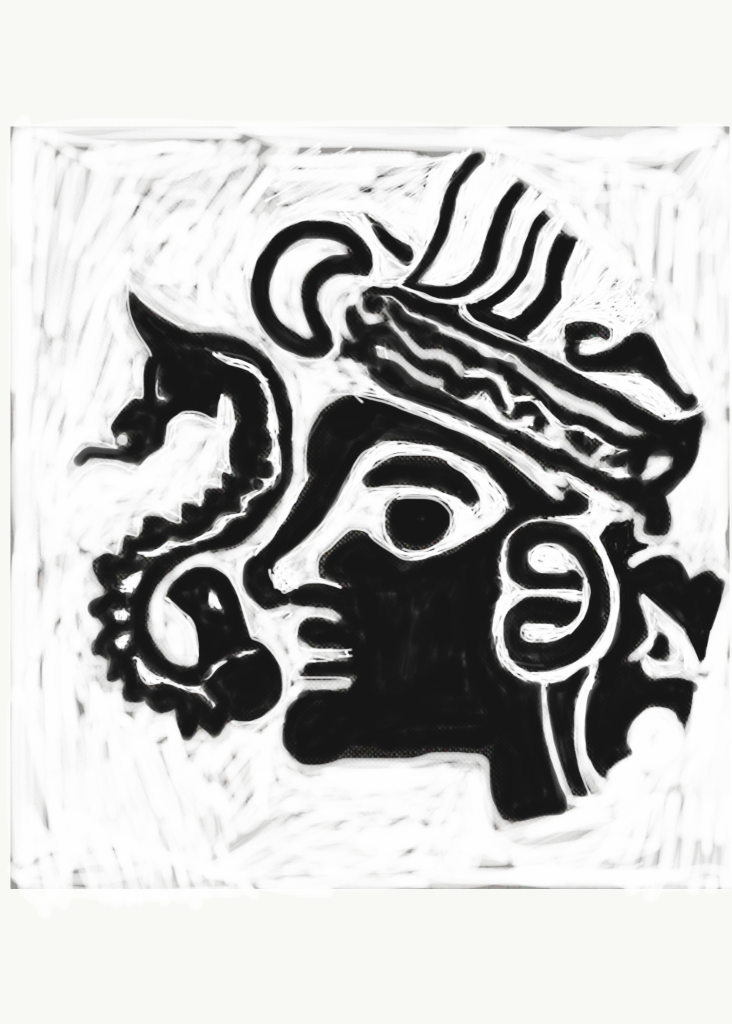

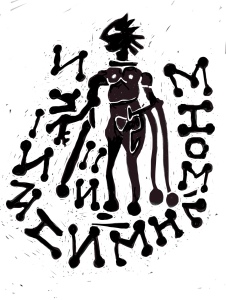

4. The figure here is greatly schematised. There is a clear celticisation of the head: it now has a big eye, a clear nose/mouth, spikey, warrior hair and a clearly depicted neck torc.

Breasts and shoulders are still emphasised. The lion-skin is now just a stylised drape over the left arm, But the right arm has become elongated to have a ‘long reach’ with particular, but difficult to interpret, protrusions that may be fingers or something else.

The ends of lines are given prominent pellets ( letters, legs, lion-skin).

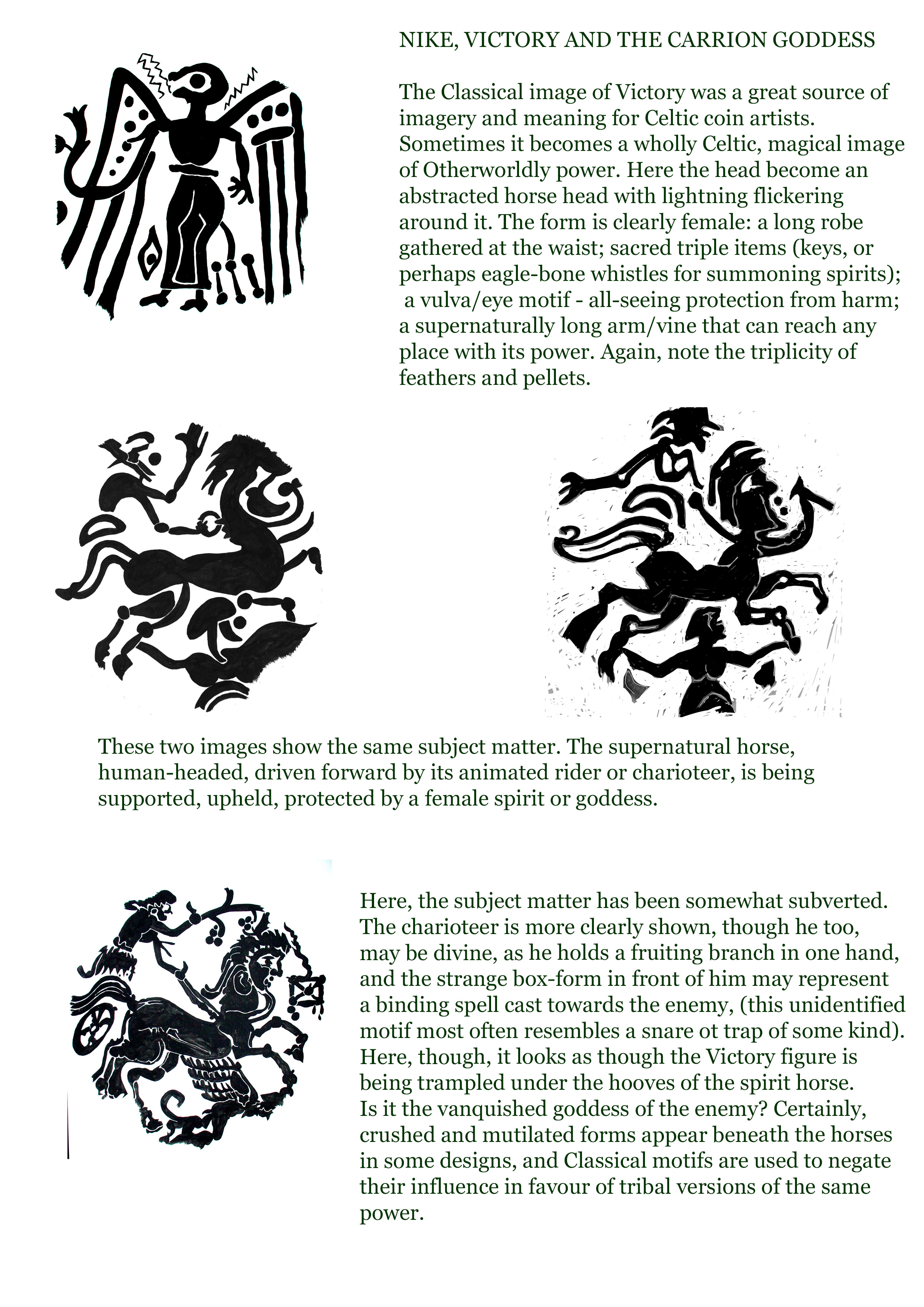

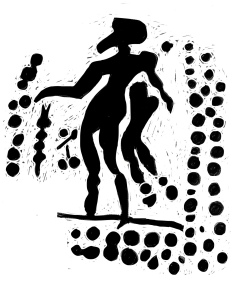

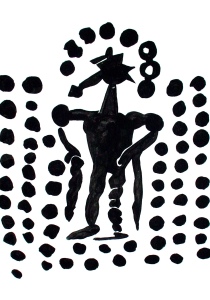

5. This design retains the sense of contraposto and Classical proportions in the figure. The club is still clearly a club, but the lion-skin has been replaced by a bow. The bow was one of Hercules’s main attributes and weapons. The figure is twisting completely round, looking backwards, head turned in opposite direction to the feet, giving the whole pose a tense dynamism despite its heavy abstraction. Note the possible single horn that is appearing on the head. Here the lettering has been completely replaced with a double row of pellets. The letters between club and leg have now become a triple pellet – sign of sacred and Otherworld power.

6. Classical pose and proportions are retained here, a nice contraposto and well-defined arms and legs. The lion-skin takes greater part in the overall design echoing the lines and movement of the figure in a pleasing, balanced way. The club no longer resembles a rough-hewn branch. It’s form is familiar to coin art, though hard to clearly interpret. It may be a sceptre or wand and its top may be suggestive of serpentine energy.

There is a strong elongation of the face and jaw. This may be a representation of a long beard ( Herakles is always shown bearded), but the animal-like profile this gives to the figure may be suggestive of some kind of transformation or shape-changing qualities.

The lettering here is a more fluid, randomised ground of different sized pellets.

The mirroring of human and animal in the human/lion and human body/animal head may be an important aspect of the message in this image.

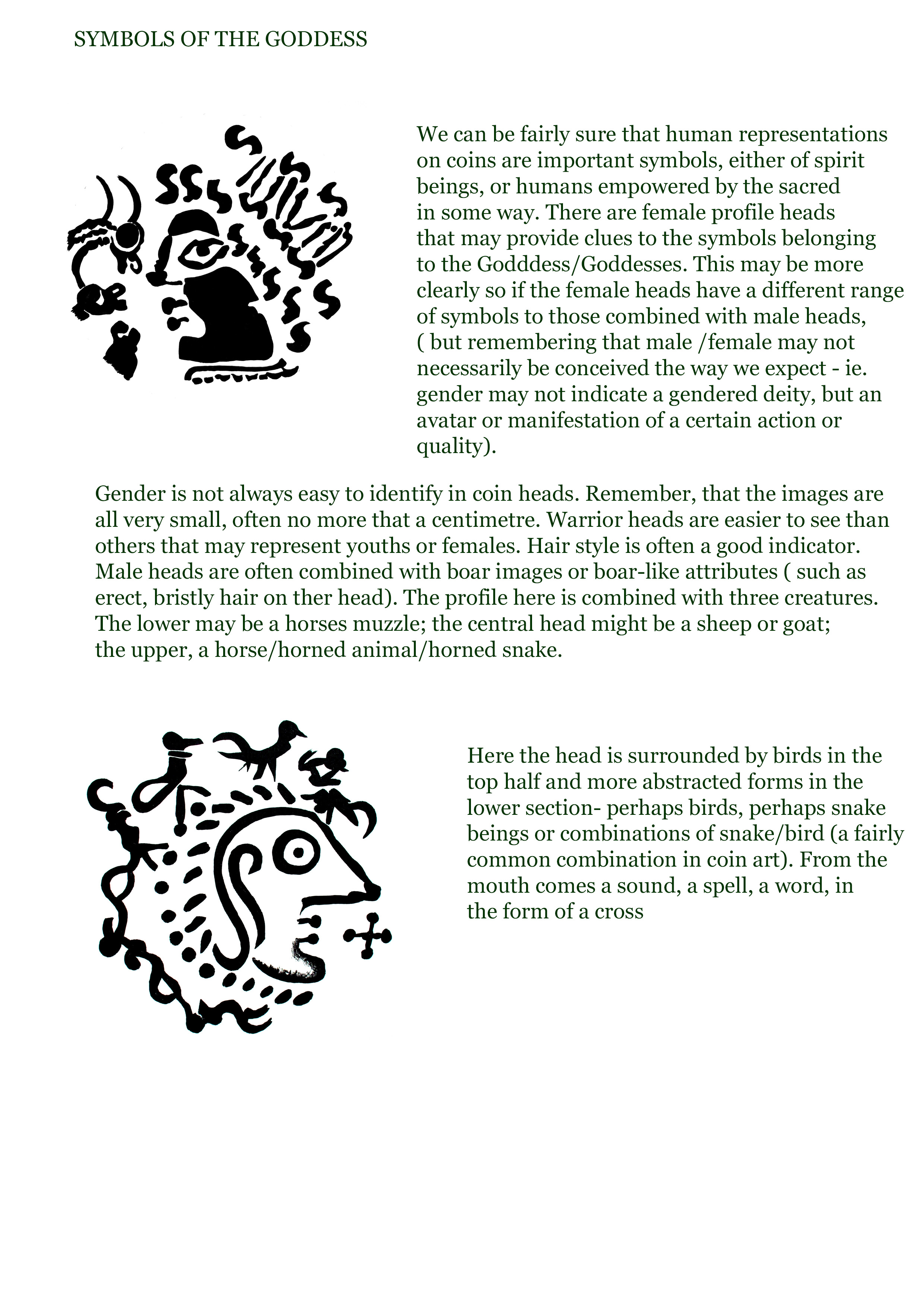

7. The figure of Herakles here is abstracted and statuesque, but all the physical characteristics are present. There is a conscious symmetry about the design with fairly precise mirroring about the central vertical axis. Both club and lion-skin are rendered as an arc of pellets. The head is just about identifiable as human but the whole feel is more hieratic and totemic. The way the two streams of small pellets meet and echo the surrounding pattern suggests a ‘pouring forth’ of blessings, power, abundance and so on. In this image the Otherworld divine certainly takes over from the Classical love of lithe, muscular, perfected masculinity. The phallic references of the elongated, domed head points to the progenitor, ancestor, fertility archetype, and is explored and developed in other Celtic coin images of Hercules, as we shall see. In all these images, the warlike attribute of the club is in a passive role, used more as a prop than a threat. Here, the originals are abstracted and, without reference to Classical types, one would not guess what they were – other than some kind of flow or emanation from the central figure.

The use of round pellets by coin artists is an interesting subject. Practically speaking, using a punch to create an indented round mark on the die is much simpler than engraving or carving a shape or line. Remember, that the working surface for coins is incredibly small, usually not much more than centimetre or two in diameter. Certainly there is a convention across coin art to terminate lines in a small punched circle. This is stylistic, but also practical : a neat way to clearly end a shape. Where there are masses of punched pellets there are several options as to specific meaning. Firstly, they provide a textured background pattern- though Celtic art is rarely concerned with showing ‘things on a background, or located in space’ as Classical art is. The Celtic artist is more focused on an integrated pattern-making that balances and plays with positive and negative space. Often the negative spaces are constructed to add to, or comment on, the objects modelled in relief.

There is a possibility that heavily pelleted grounds represent some quality of significant elemental solidity – earth, water and so on. This provides a whole development of possible meanings for images where these pellet grounds occur. If we ignore the prototype of Greek alphabetical text, what might these marks in this design now mean? Apart from amorphous and difficult to portray substances, such as light, darkness, earth, water, cloud, vapour, mist, air, stars, round pellets also reflect the circular nature of the coin itself and thus by correspondence to wealth, abundance, power, blessing, authority, seed, harvest, obligation, richness, the Land, numbers ( specific, as in triplicity, and general, as in manyfold, numerous, uncountable).

8. Another abstracted, statuesque totem. The emphasis here is on the large eye and the echoing ring pellets placed symmetrically around the figure. The Greek lettering has taken on a much more characteristic range of Celtic coin motifs that may or may not have fixed and understood meanings to the observer. Ring pellets may be solar symbols; dumbbell rods are commonly found and definitely suggest an object that has presence and weight, a ritual tool or piece of insignia;

groupings of three pellets commonly seem to indicate the special or sacred; groups of five- a square with a central pellet are also common, perhaps relating to the pentagram that was later In Medieval times associated with druid knowledge.

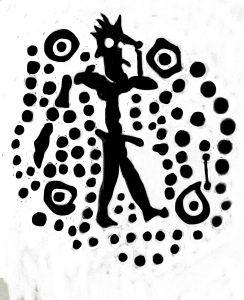

9. Here we have a continuation of the similar theme: a figure framed by four solar ring pellets on a field of other more or less same sized pellets. The figure is more dynamic, clearly moving off towards the right. The shoulders are emphasised but the arms are much less prominent. There is a hint that these may also be wing-like forms. The profile head has spiky hair and a prominent eye. The nose, lips/beard are at the same angle as the phallus and are also phallic in shape. There is a much greater sense in this design that the figure is integrated or emerging, or dissolving back into, the swirled lines of pellets around it. The presence of the ring pellets continually pull the viewer’s attention to them and they easily become staring eyes in a mysterious numinous face.

10. This design combines major aspects of both the Classical depictions and the Celtic interpretations. We have the club, the lion-skin, the broad, muscular shoulders. The figure in embedded in a regular field of pellets, with an additional halo of pellets arcing around the head. Spiky hair and phallic nose are emphasised. There is an interesting difference in the depiction of the legs: the left leg looks as if it is damaged or withered. There is no practical reason why the legs should not be drawn in the same way, so we can assume that the difference was intentional and significant. It could be argued that the ‘contraposto’ pose has simply been misinterpreted, and that the different angle and outline of the left leg was read as a malformation. Alternately, the staff/club, often shown as a support, may have suggested a more elderly, war-worn ancestral figure, or one who is magically ‘other’ or set apart from normal beings

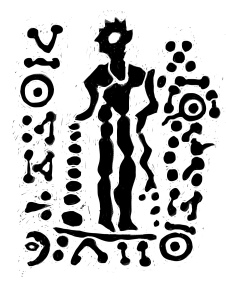

11. This Herakles moves a long way away from the Classical, away from the human hero towards the numinous and ambiguous Otherworld being. Only the presence of the club, held in the right hand and resting on the ground, points us towards the Classical prototypes. Even that has its own peculiar doubling up of its knobbly shape. The symbol/Greek character between club and leg is now definitely the triple pellet of sacred presence. The other Greek letters have become familiar Celtic motifs. Note the torc below the feet, and, of course, the six-pointed star to which the figure seems to be gazing.

The profile head still possesses a prominent chin or beard and a long nose, but now there seems to be a clear pair of horns on the top of the head. The lion-skin is gone, replaced by a long tail that echoes the shape of the arm above, though this arm could be interpreted as a wing just as easily.

The pellet at the armpit is a real focus for the attention, and it also creates what resembles a long-necked bird’s head in the negative space there.

So here is a fully transforming, ambiguous Celtic Otherworld being: part human, part animal, part bird, part cosmic being.

There is still a sense that the figure is bestowing power or other blessings ( the pellets flowing away from the arm/wing; the pellet-like club; the symbols of wealth and power beneath its feet). These is a certain intensity in the portrayal of the head and star – it definitely seems to be the focus of the figure’s attention, almost to the exclusion of all else. The star was used in Roman coinage to symbolise apotheosis of emperor to god. The star in Celtic coin art is rather more ambiguous. Does it here represent a star deity? Or the ancestral progenitor as both a chthonic giant and a celestial presence?

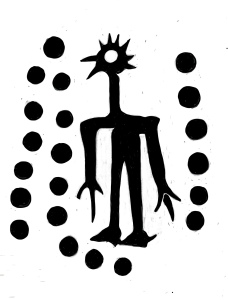

12. The last image from this selected group clearly derives from the Herakles type, but is very simplified and has characteristics that emphasise a very different archetype – that of the Bird-Man-Spirit. We saw the iconographical shift take place in the last image, but there, the human was still present. Now the head is vehicle for a large staring eye, framed by a comb of spiky hair that is suggestive of a coxcomb. The long nose and chin now is transformed into an open bird beak. The arms, still with prominent shoulders, now terminate in birdlike, triple clawed feet, whilst the feet are also birdlike with maybe a hint of a spur at the heel. The warrior as wild boar is the commonest representation, but there is also a notable number of warrior-as-cockerel images. Both creatures share important characteristics: the razor-sharp bill/tusks and claws/feet; the erectile spinal bristles of the boar and puffed up feathers of the cockerel when threatened or in combat; the aggression and display; the relentless territorial protection of their offspring.

As well as these images from the Eastern Celts, there are also one or two possible Herakles images from Gaul. The attributes ( club, lion-skin, posture) are less certain, but we should consider that the similar imagery may also indicate, if not Hercules himself, then the archetype of a semi-divine progenitor, guardian spirit and model of the heroic defender of the people.